Seagrass: Large Enough to See from Space but for How Long?

A boat mired in the mud isn’t an unusual occurrence here in Maine. In this part of the world, tidal ranges in the 9-11 foot or greater range commonly happen twice daily. The tidal swings are nearly twice as big in the Bay of Fundy, only a few hours drive from here in the northeastern end of the Gulf of Maine. When the tide recedes, an underwater world is laid bare. Crabs scurry about in the mud seeking a spot to bury themselves. Squirts of water like mini fountains erupt from the drying surface, an indication that clams are below. Also evident is a meadow of seagrass, home to a host of species from microalgae and worms to mollusks and crabs. These meadows are among the most productive ecosystems in the world. They form the backbone of coastal ecosystems. The U.S. designated them as “Essential Fish Habitat (EFH) and a Habitat of Particular Concern under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act in 1996.” While many people are aware of global warming, far less know about what seagrass is, what is happening to it and why it is of serious concern.

What is Seagrass?

What is seagrass?

Seagrass, also referred to as eelgrass, is the only flowering perennial that grows in marine environments. Seaweeds, unlike seagrasses, are algae and not flowering plants. Seagrass grow in soft substrates like mud and sand. They are found in both areas that are exposed at low tide and those that are 23 feet (7 meters) in depth. There are 72 species of seagrass with Zostera marina being the most commonly found species in the Northern Hemisphere. Seagrasses can form dense underwater meadows, some of which are large enough to be seen from space.

Eelgrasses originated in the Pacific Ocean between ten to five million years ago and “spread to the Atlantic Ocean starting around 3.5 million years ago, before the most recent ice age hit and ice sheets separated the two oceans.” Scientists have studied the similarities and differences of eelgrass living in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Eelgrass ecosystems in the Pacific are characterized by sparsely populated meadows with meter-high plants compared to the Atlantic where the meadows are denser with shorter grasses. The most striking difference is that the “eelgrass ecosystems in the Atlantic have far less genetic diversity than in the Pacific…Atlantic eelgrass’s lack of genetic diversity might be bad news for its ability to survive climate change…Given enough time, Atlantic eelgrass could eventually evolve to have the same breadth of diversity as its Pacific counterparts. Unfortunately, the swift pace of climate change may not give it that chance.”

The different species of seagrass come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Some look like traditional grass blades, others like tree leaves, and others are long and narrow. Seagrasses can be found in the shallow seas along the continental shelf of all continents except Antarctica. The key factors for seagrass growth is the availability of light because seagrasses need sunlight for photosynthesis, a chemical process where sunlight is transformed into food energy.

Seagrass meadows declining at alarming rate worldwide

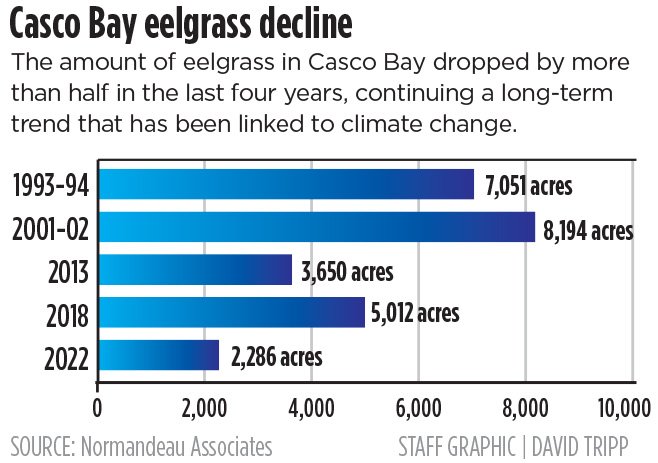

A recent study conducted for Maine’s Department of Environmental Protection found that the eelgrass meadows in Casco Bay, an inlet of the Gulf of Maine along the southern coast of Maine, declined by more than half during a four year period. From 2018-2022, coverage dropped from 5,012 to 2,286 acres.

“We were aware of the decline in eelgrass, but we thought we had some time to think about this. But we lost 54% of eelgrass in the last four years. The time to act was yesterday,” said Ivy Frignoca, Casco Baykeeper for the environmental group Friends of Casco Bay.

The decline is not limited to Casco Bay. The trend is particularly worrisome along the eastern shores of North America, especially in the Gulf of Maine where water temperatures are increasing at a disturbing rate. Last year was the second warmest on record for the Gulf of Maine, almost four degrees above the long-term average. According to the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, the average annual sea surface temperature was 53.66 degrees Fahrenheit.In fact, the Gulf is warming faster than any other body of water on the planet except for an area northeast of Japan. While many people are aware of global warming, far less know about what is happening to seagrass, why these consequences are of concern, or even more basically what seagrass is.

Why is seagrass important?

Seagrass meadows play a number of vitally important roles; in short, they are critical marine habitat. Eelgrass is the foundation of a highly productive marine food web. Their degradation results in increased coastal erosion, wave action, and ocean acidification as well as declines in commercially important fish and shellfish species, water quality, and carbon storage contributing to further effects of global warming. “Eelgrass meadows protect the coast, store carbon, and support a host of organisms, from economically important herring, sea bass, and lobsters to vulnerable species such as sea turtles and dugongs. Zoom in closer, and you’ll find a metropolis of algae and tiny invertebrates clinging to each gently swaying blade.”

Seagrass meadows are being lost at a rate of around 7% annually, equivalent to two football fields every hour. This loss is attributed to many variables, among them are climate change, coastal development, pollution, overfishing, and other anthropogenic, human-caused, factors. “Poor water quality (particularly high levels of nutrients) caused by pollution is the biggest threat to seagrasses around the world. Water quality problems are particularly serious in countries that are growing rapidly, but where there are not many laws to regulate pollution or for seagrass protection.”

For a myriad of reasons, the impact of warming water temperatures cannot be ignored. In 2021, the Gulf of Maine’s largest puffin colony only had 6 percent of puffin hatchlings survive the nesting season. That number is a stark comparison to the typical survival rate of 75 percent. The young birds starved to death because of a lack of availability of food. Rising water temperatures are also a concern to Maine’s lobster fishery. As a whole it foresees a potential negative impact on their billion dollar industry.

Warming waters directly impact seagrasses. Warm water leads to algae blooms. The blooms cloud the water making it difficult for seagrass to get sufficient sunlight for photosynthesis. Warming water temperature also favors the invasive green crab. The young crabs eat the seagrass while the adults pull it up by the roots while foraging for soft-shell clams. Frignoca observed that “Water temperatures may be reaching the point where eelgrass can no longer survive.”

What can be done?

Across the globe, people are working to understand the problem of declining seagrass meadows and find ways to assist in its restoration. Nicole Kollars, an ecologist at Northeastern University in Massachusetts, suggests “moving seeds and plants around to increase gene flow or by using eelgrass nurseries to support restoration efforts.” Attempts to rebuild and restore seagrass beds have been undertaken “by planting seeds or seedlings grown in aquaria, or transplanting adult seagrasses from other healthy meadows. Some of the most successful restoration stories come from the Chesapeake Bay and coastal Virginia in the Eastern United States where, through 2014, the Virginia Institute of Marine Science has seeded 456 acres with 7.65 million seagrass seeds. As of 2015, the seagrass Zostera marina has increased from these seeded plots to cover 6,195 acres. Seagrass restoration in Tampa Bay, Florida, has also experienced important success including improvements in water quality and the associated fish community. For restoration to work, it is critical that the causes of the original decline in seagrasses have been eliminated.”

In Maine, Glenn Page, an interdisciplinary conservation scientist/practitioner with nearly three decades of experience building coastal and marine ecosystem stewardship, is taking a broader approach. He has launched a bioregional movement. His Team Zostera is hosting a meeting in July in Portland, Maine. The gathering will consider regional ways to address the multiple challenges that are impacting seagrass meadows. Page believes “seagrass meadows are the ‘canaries in our coal mine’ and have a big story to tell if we are able to listen.”

Whether the focus of restoration is on local seagrass beds or more broadly encompasses a region, the bottom line is that seagrass populations across the globe are in trouble. Individuals can exert their own agency in the work that needs to be done to protect seagrass meadows. Avoid littering. Don’t dump hazardous materials down the drain. Limit the use of fertilizer and pesticide. When boating, avoid shallow areas, reduce wake near land, and avoid dragging an anchor in seagrass.