Off again, on again protections: Will the North Atlantic right whale survive the legal wrangling?

Since 2011, the endangered North Atlantic right whale population has declined 30 percent, down to less than 340 animals. New regulations to protect the critically threatened whale, established by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration after years of research and public hearings, have become entangled in a legal battle with Maine’s lobster fishing industry.

There’s been a legal wrestling match going on in Maine in the US, and the survival of the North Atlantic right whale hangs in the balance. The two opposing sides are Maine’s lobster fishing interests and conservationists concerned about the right whale’s increasingly dire situation.

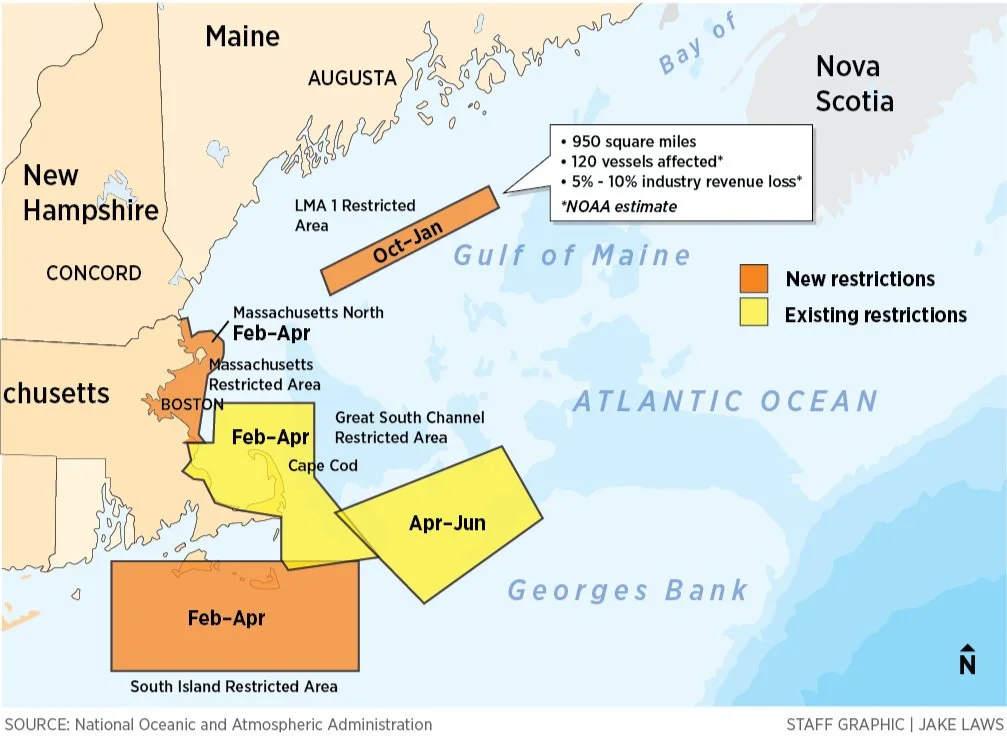

Fishing interests are fighting rules issued earlier this year by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which were developed after years of research and public input, barring the traditional rope-and-buoy lobstering method in designated areas during the months of October through January. The prohibition is intended to reduce the chances that any more of the already endangered whales perish from entanglements in fishing gear.

The North Atlantic right whale population was estimated to be around 480 in 2011. In the ensuing decade, the population has declined by 30% with that number now dropped to fewer than 340 individuals. Research published by New England Aquarium in October 2021 revealed that 86% of known right whales had scars caused by entanglement in fishing gear. Additionally, the study showed right whale body lengths have declined in the last 40 years, suggesting that entanglements, if they don’t kill the whales, cause stress that rob the whales of energy needed to grow and reproduce.

At one time, commercial whaling had been important to New England’s economy. As the whaling industry adopted new technologies, it became more deadly. The result was a precipitous decline in whale populations. In 1971, the US officially outlawed commercial whaling at a critical time when it was estimated that as few as 100 right whales remained. Because of their depleted numbers, right whales were listed as endangered and are protected under a variety of laws including the Endangered Species Act. Under the act, a federal plan for the species’ recovery and protection was developed after years of research and public input.

Currently, the lobster industry contributes USD $1.4 billion to Maine’s economy. The lobster industry has been lobbying hard against the plans developed by federal agencies to protect the whales. The Maine Lobstering Union, with the support of others, went to court to seek legal relief from NOAA’s restrictions. In October, US District Judge Lance E. Walker granted a temporary restraining order and a preliminary injunction which effectively halted closure in the designated area. The decision was temporary and was supposed to allow the science behind the rules to be evaluated.

This move was then countered by an appeal by the National Marine Fisheries Service and conservationist groups. They asked the court to reinstate the closure citing new information. The data shows that the right whale population has continued to decline by another 10% from 366 in 2019 to 336 in 2020. However, a district court denied the motion but an appeals court ruled in favor of the whales. The appeals court ruling said that the lower court had overstepped its authority because Congress had charged federal agencies with protecting the endangered whales.

“While there are serious stakes on both sides, Congress has placed its thumb on the scale for the whales,” appellate judges William Kayatta, David Barron and Gustavo Gelpi wrote in their decision.

Maine’s Governor Janet Mills has pledged to support Maine lobstermen who contend that the financial costs of the ban are too high. The lobster industry argues that the ban will financially impact as many as 200 lobster boats. The result may be that the fisher folk lose as much as half their annual earnings. These boats make top-dollar during the proposed ban between October to January, a period during which the number of lobster caught is reduced while there is an increased demand due to the holiday season.

Environmental advocates like the Conservation Law Foundation counter with the argument that the ban comes at a particularly critical time for the future survival of the North Atlantic right whale. Since 2017, NOAA has documented nine North Atlantic right whale deaths and another 14 injuries due to entanglement. An additional 11 have died after being struck by vessels. In total during the last four years, 50 deaths have occurred. This is particularly devastating given the already depleted right whale population.

The Legal Battle is Likely to Continue

The Maine lobster industry has vowed to continue the legal battle. On Nov 17, the Maine Lobstermen’s Association launched a three-year, $10 million fundraising campaign. The “Save Maine Lobstermen” campaign aims to raise money to fight against the regulations that industry members say could “eliminate the fishery and end Maine’s lobstering tradition.” Alfred Frawley, the union’s attorney, has stated that just because Maine is responsible for roughly 95% of the lines in the water, it doesn’t mean the blame for the problem should fall on Maine’s lobster industry. The industry claims there is an absence of proof to support the notion that entanglements and whale strikes are occurring in Maine and suggests that the focus should be on Canadian waters.

Virginia Olsen of the Maine Lobstering Union in association with other industry advocates criticized the statistical modelling used by federal agencies to develop the seasonal lobster ban. Olsen argues that more evidence is needed to prove that right whales actually spend time in the areas that are to be closed to rope-and-buoy fishing. In rope-and-buoy lobster fishing, buoys are used to mark the underwater location of traps. Ropes that connect a buoy to a trap can ensnare whales resulting in physical harm and even death. Olsen contends that right whales are found offshore beyond the closed area and that no hard data exists to link lobster gear used in Maine waters with the death of right whales. In addition to the seasonal closure, the new rules require that state-specific markings be attached to gear and that weak points be inserted on ropes to make it easier for entangled whales to break free. These rules, unlike the area ban, aren’t set to go into effect until May 2022.

Will the North Atlantic Right Whale be Doomed to Extinction?

A coordinated and immediate action along the entire whale’s range, not just Maine, is needed to eliminate entanglements with fishing gear and reduce strikes by vessels.

With a rapidly declining population, there is precious little time to act.

The survival potential for the right whale is not determined by the total number of whales; instead, it is the number of extant males and females capable of breeding. This number must be large enough that the whales can find mates as well as adequate protections to assure calves will grow and thrive, and eventually be able to breed and produce new offspring.

There are additional factors that negatively impact the whales that humans have little or no control over, foremost among these is climate change.

If these things cannot be mitigated, it is unlikely that the North Atlantic right whale will survive.

North Atlantic right whales are perilously close to extinction, but there is still hope. It is vital that advocates demand action.

“There is no question that human activities are driving this species toward extinction” said Dr. Scott Kraus, chair of the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium. “There is also no question that North Atlantic right whales are an incredibly resilient species. No one engaged in right whale work believes that the species cannot recover from this. They absolutely can, if we stop killing them and allow them to allocate energy to finding food, mates, and habitats that aren’t marred with deadly obstacles”.

This article first ran Dec. 3 on earth.org.